Has The Bible Been Lost In Translation?

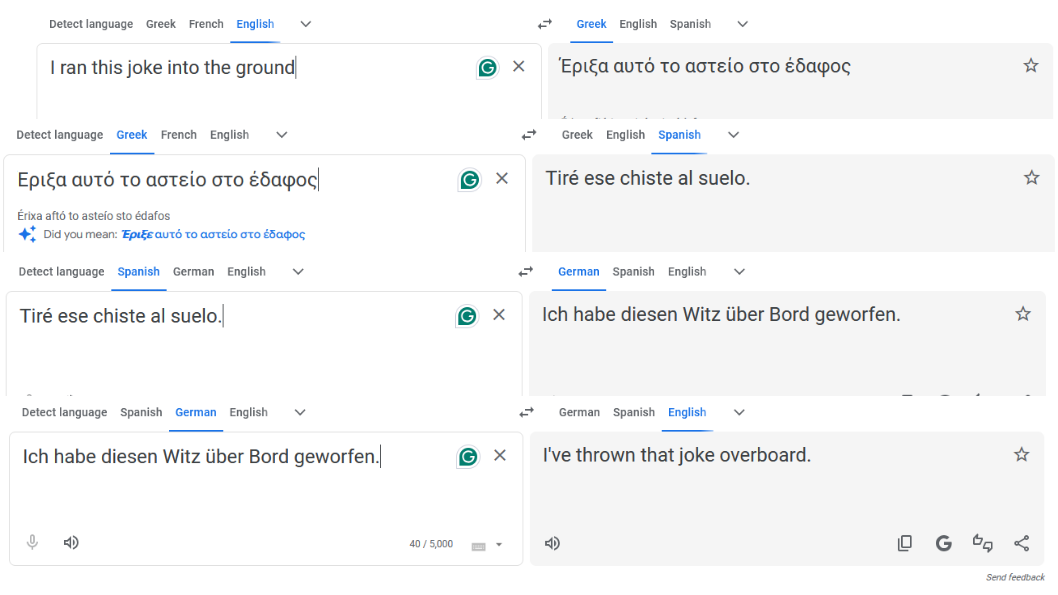

Here’s a fun experiment. Take a sentence in any language and then use Google Translate to translate it into another language. Take that result and translate it again. Do it one more time. Now take that result and translate it back to the original language. Chances are, you don’t get back the original sentence you started with.

Now consider this. The authors of the New Testament wrote in Greek. For almost a thousand years, the church used a Latin translation of the Bible. 400 years ago, the Bible was translated into English, but it was full of these and thous and thys. 300 years later, it was translated into more modern English. And, to this, there seems to be no end because new translations come out every year where a word here and there is “updated”.

Does the Bible face the same challenges as our translation experiment? Have the original words of Jesus been altered in this process? Can we trust that what we have today are the things he actually said and the things he actually did?

When I was still a skeptic of Christianity, this translation problem was something that kept me from trusting the Bible. This is something that occurred to me early in life, when I was still a teenager and still actively attending church every Sunday. The issue with this challenge is that this isn’t how Bible translation works.

Bible translators don’t translate from one language to the next; whenever a new translation is being done, the translators start with the EARLIEST language they have. That’s Greek. So, the path is from Greek to modern English – not Greek to Latin to KJV to 1800s English to 1900s English to 2025 English.

Here is a VERY brief history of Bible translation. The earliest manuscripts of the New Testament were written in Greek. It was the primary language of the Roman Empire. As the manuscripts circulated in the area, they were translated into local languages, including Latin, Coptic, Syriac, Georgian, Gothic, Arabic, and many others.

There are a few different minor translations in the first few centuries. We have the Syriac Translations starting in the 2nd Century, the Gothic Bible in the 4th century, the Coptic Translations in the 3rd-4th century, and the Ethiopic Bible from the 4th-6th century.

By far, the most impactful translation of the Bible in the first few centuries is what is called the Latin Vulgate. There is a fascinating story on this translation well worth diving into, but for our purposes, all you need to know is that the Greek manuscripts were translated by Jerome into Latin between 382-405 CE at the request of Pope Damasus I. The Latin Vulgate became the standard translation of the Western Church for centuries.

It wasn’t until 1382 that we had the first Bible translation in English. This is known as the Wycliffe Bible. 200 years later, in 1526, we get the Tyndale Bible in English. Why was there such a gap? Because the Roman Catholic Church condemned the use of any other translation besides the Latin Vulgate. Wycliffe and Tyndale were both condemned for their work. Tyndale was actually executed because of it.

Then, in 1611, one of the most significant books of the English language, let alone Bible translations, was produced, and that is the King James Bible. It was a major undertaking, officially backed by the Crown, and became THE English translation for the next 350 years.

It wasn’t until 1952 that we saw the next notable English translation, the Revised Standard Version. The 20th century saw an explosion of English translations. Now, we have the NIV, the NASB, the ESV, the NLT, and so many more.

It’s important to note that in almost every case, the Bible translators of these Bibles I mentioned started with the most up-to-date collection of Greek manuscripts that have been discovered. The translators always started with the source language, Greek. Not the language that preceded the edition they were translating.

The only exception to this was the Wycliffe Bible. John Wycliffe’s translation was an English translation of the Latin Vulgate. But all of the other translations came directly from Greek.

A perfect example of using updated scholarship is the Revised Standard Version. A lot of new manuscripts had been discovered since 1611, when the KJV was published. So, the translators wanted to both update the English of the KJV and use older manuscripts that have been discovered (including the Dead Sea Scrolls).

Once I learned how the translation process worked, I realized the English Bible I was reading was as close to the original Greek as modern scholarship would allow. I didn’t have to worry that the words of the original authors has been lost or corrupted during the translation process.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

latest video

news via inbox

Subscribe and never miss an update!

Wow! I love how the translation is directly from the most up to date Greek to Modern English. That really strengthens my faith. Thank you Mr. Gilmore.

You’re welcome!

Thank you this was really helpful and helped me understand the history and why the translation is important

Great! Glad it helped.